(Click HERE)

INEZ WALKER in GALLERIES, EXHIBITIONS

and on the WEB:

(Updated: February, 2024)

Smithsonian Institution

American Folk Art @ Cooperstown

American Folk Art Museum

Marna Anderson ("Lady with One Flower")

Marna Anderson ("Lady with Two Flowers")

Archives of American Art

Art Net

Art Net

Ask Art.com

(summary)

Ask Art.com

(examples of her work)

Ask Art.com

(book references)

Biggin Gallery, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama

(February 9 to March 5, 2004)

Bethany Mission Gallery

Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art (Intuit)

The Corcoran Show Revisited

(NY Times subscription required)

Diattaart

Encyclopedia of American Folk Art

Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center (Frontal Man, 1976, Pencil, colored pencil, and felt-tip pen on paper; Gift from the collection of Pat O’Brien Parsons, class of 1951)

Intu Outsider Art

Old Dominion Univ.,

Gordon Galleries

Phyllis Kind Gallery

Smithsonian Biography

Smithsonian Collection

Vassar College

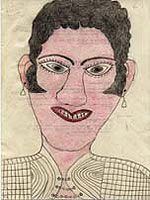

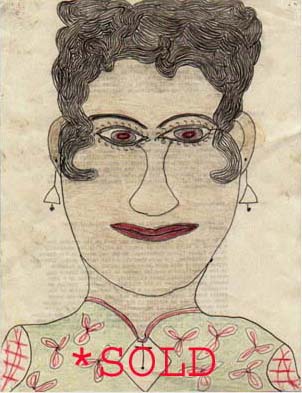

Bad Girl w/ Earings on Prison Mimeo #5

(**SOLD**)

What is Outsider Art?

What is Self-Taught Art and Art Brut?

SELF-TAUGHT, OUTSIDER & FOLK ART LINKS:

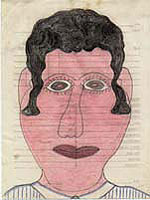

Bad Girl w/ Long Nose on Prison Mimeo #6

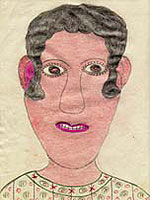

Patterned Dress on Plain Paper #7

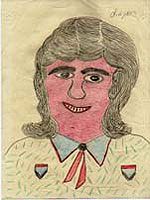

"Diapers" on Plain Paper #8

America Oh Yes.com

American Folk Art Museum, New York

(Exhibition: September 14, 2005 to March 19, 2006)

Anton Haardt Gallery

Art Net.com

Art Resources.com

At Home Gallery.com

Bayley, Elizabeth

(personal notes)

Davenport, Ray:

Davenport's Art Reference

Focal Art.com

Lynda Roscoe Hartigan.Made with Passion: The Hemphill Folk Art Collection in the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C. and London: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990).

House of Blues

Johnson, Jay/William Ketchum: American Folk Art

Livingston, Jane/J Beardsley: Black Folk Art in America

Louise Ross Gallery

Maresca, Frank: American Self-Taught

Phyllis Kind Gallery

Roche, Jim, FL State Univ.

Rosenak, Chuck & Jan: Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists

Self-Taught Art.com

Slotin Folk Art

Smithsonian Online

Univ. Press of Mississippi

copyright 2002-2024

Don Bayley,

member:

Hosted by

FYI World Media

('The Corcoran Show Revisited,' ROBERTA SMITH, NY Times, March 8, 2002)

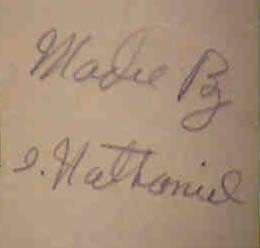

Presenting the early work of Inez Nathaniel:

drawings made while confined at

the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, Bedford

Hills, NY

Folk artist? Artist Brut? Outsider? Visionary? Intuitive? Self-taught? Inez Nathaniel Walker was all of these and none of these. Inez' art is unique. Born into poverty as Inez Stedman in Sumter, South Carolina in 1911, she

was orphaned at an early age, married when only 16 years old and

quickly had four children. During the Great Migration of the 1930s she moved

to Philadelphia to get away from grueling farm work.

Folk artist? Artist Brut? Outsider? Visionary? Intuitive? Self-taught? Inez Nathaniel Walker was all of these and none of these. Inez' art is unique. Born into poverty as Inez Stedman in Sumter, South Carolina in 1911, she

was orphaned at an early age, married when only 16 years old and

quickly had four children. During the Great Migration of the 1930s she moved

to Philadelphia to get away from grueling farm work.

"Got tired of working so hard on the farm, weeding and hoeing," she told a reporter for New York State's "Correctional Services News" in 1978. "The muck would eat you up."

For awhile Inez worked

at a pickle plant, but a strike brought that to

an end. In 1949 she moved to Port Byron in New York State and went back to

migrant farm work but at least the "muck" of South Carolina was missing.

She lived and worked in several other places in New York, including Clyde,

Savannah and Geneva.

For awhile Inez worked

at a pickle plant, but a strike brought that to

an end. In 1949 she moved to Port Byron in New York State and went back to

migrant farm work but at least the "muck" of South Carolina was missing.

She lived and worked in several other places in New York, including Clyde,

Savannah and Geneva.

In the late 1960s Inez was Convicted of criminally negligent homicide and imprisoned for killing a man who had most-likely abused her. "Some of these men folks is pitiful," Inez told the newspaper reporter. It was while confined at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility (formerly known as Westfield State Farm) in Westchester County, New York State that she began to draw, perhaps to isolate herself from the "bad girls" in the facility.

One day Elizabeth Bayley, a teacher of remedial English at the prison for women, found several drawings that had been anonymously left in a pile on a chair in her classroom and discovered they were done by Inez Nathaniel, a student in her class. There were 79 works in all, drawn on the backs of any paper Inez could find such as the prison newsletter, some prison evaluation sheets and forms. Mrs. Bayley was astounded by Inez's visionary talent, "Looking over them, I was struck by their originality, their humor and their amazing attention to detail," the teacher said. "I offered to buy them from her. She was delighted to accept, so I contributed the money to her account at the prison commisary."

Mrs. Bayley also brought Inez's work to the attention of the art teacher who supplied her with drawing paper and sketch books, pens, pencils and crayons. About twenty of the works represented on this web site are on plain paper, these are the very early drawings. Others were done a bit later at the prison and are on art paper.

Drawing obsessively and prolifically, Inez, in just a few months, filled dozens of sketch books prior to her release from prison in 1972. Mrs. Bayley showed the drawings to Pat Parsons, a local folk art dealer, who purchased many of them for exhibition and soon Inez had her first show. Pat Parsons supplied Inez with first-rate materials: good paper, watercolors, pencils (both colored and graphite), ink crayons, and felt markers. These are reflected in her later work.

On this website

we are featuring Inez Nathaniel's very early works. These drawings, all

done at the prison, are from Mrs. Bayley's private collection. You can

clearly see the typed information from the correctional facility

mimeographed forms showing through from the reverse side.

On this website

we are featuring Inez Nathaniel's very early works. These drawings, all

done at the prison, are from Mrs. Bayley's private collection. You can

clearly see the typed information from the correctional facility

mimeographed forms showing through from the reverse side.

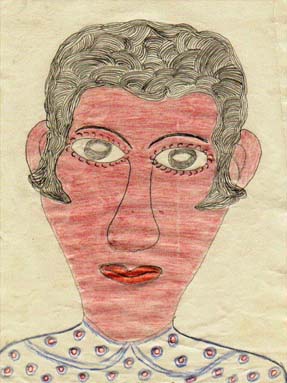

Inez's drawings are almost exclusively single or paired portraits of females. In most of her works, the heads are drawn much larger and more expressively than the rest of the figures and dominate the composition. The hair is elaborately detailed and the drawings include lots of patterning. The eye lashes are an Inez Walker specialty as are her forward-facing eyes in profile drawings. Though Walker never felt she was able to capture a likeness, and she relied on her imagination to develop the faces, she created clearly recognizable characters. Some recur frequently. Elements of self-portraiture are also evident in her figures, many of whom wear clothing, especially hats, based on the artist's own.

In many of her works, Inez Nathaniel drew the people around her, mainly the inmates whom she referred to as the "Bad Girls." The bad girls are often depicted in social situations engaging in the pleasures of drinking, smoking and conversing. Men and children only occasionally appear in her work.

Inez Nathaniel remarried in 1975 and took her new husband's name, Walker. She lived quietly and simply in a small city in New York's Fingerlakes region, continued to draw and was glad to have the chance to show what she had done to visitors. She died in 1990 in Willard, NY.

Inez Nathaniel-Walker is included in Chuck and Jan Rosenak's "Museum of American Folk Art: Encyclopedia of 20th Century Folk Art and Artists" and "Contemporary American Folk Art: A Collectors's Guide." She is listed in the Gold Edition of "Davenport's Art Reference," Jane Livingston and J. Beardsley's "Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980," "The Artists Bluebook," Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco's "American Self-Taught: Paintings and Drawings by Outsider Artists" and Jay Johnson and William Ketchum's "American Folk Art of the Twentieth Century."

Her work is represented by numerous galleries. Her drawings are in the Collection de l'Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, the L'Arcanie, Neuilly-sur-Marne, near Paris as well as in a number of museums in the United States such as the Museum of American Folk Art, the Museum of International Folk Art and the Smithsonian. Since the early 80's Inez has been included in almost every major folk art book and catalog that includes the work of black folk artists.

We are pleased to offer via this website, INEZ WALKER.com, many of the original drawings from Elizabeth Bayley's personal collection.

COMMENTARY:

JOHANNA BLUME, Cooperstown Graduate Program as part of her elective course in American folk Art (excerpted) Walker was known for her use of lines and patterns, often filling the page with them. The subjects of her drawings – it is not clear whether they depict the “bad girls†who surrounded her in prison – are rendered in a compelling and curious manner with an extraordinary attention to detail, something typical of folk artists. One of the most striking aspects of a Walker drawing is the eye. The vast majority of her subjects possess the same oversized eye that faces forward, regardless of the direction the body faces. The eye dominates the page in part because Walker always began by drawing the face and head, and then worked her way out until she ran out of page. Walker disappeared from society around 1980. Sadly, Pat Parson found her several years later, in the Willard Psychiatric Center in Willard, New York. Walker was in and out of the center for the last four years of her life, and died there in 1990. She left behind a collection of work remarkable in its size and consistency as well as in the remarkable manner in which the eyes engage the viewer. Clearly that is where the artist looked first to take the measure of a person. |

From The New York Times, August 21, 1988 By VIVIEN RAYNOR (excerpted) THEY are called naive, primitives, folk artists or outsiders, but ''para-artists'' might be a more accurate term. After all, these untutored painters and sculptors work without conscious reference to conventional art yet somehow parallel to it and, anonymously, they have exerted an enormous influence on it. Most such artists find their avocation in middle or old age, and while some see it as a divine calling, others do it for self-expression or for profit. The demand for ''unspoiled,'' childlike art has grown steadily since Picasso discovered le Douanier Rousseau in the early 1900's, at the same time that he himself was transformed by the influence of tribal art. It doesn't hurt, either, that other modernists, notably Max Ernst, espoused the work of the deranged or that later Jean Dubuffet produced his own version of what he called ''art brut.'' Though blacks have played a large part in the development of American folk art, it is only in the last few decades that they have been singled out for attention. At the Aetna Institute Gallery in Hartford, the focus is on black women - nine of them gathered under the title ''Women of Vision'' and the majority well-known to folk art enthusiasts. Pattern is everything to Inez Nathaniel-Walker, who began drawing while serving a short prison sentence for killing a man who apparently had abused her. Done in crayon, pencil and felt tip, these lacy drawings are all portraits and in most cases the subjects are white. Mrs. Walker's reason for making art was, she said, to protect herself against the ''bad girls'' she met in prison. The girls in the pictures are basically all the same, pug-faced pink creatures with mops of curly hair who bear no resemblance to their maker, whom photographs show to be an elegant woman with an American Indian cast to her handsome face. When her work was included in the Corcoran Gallery's great black folk art roundup of 1982, Mrs. Walker was listed as living in Georgia, but in the biographical material here she is said to have disappeared. |

From Museum of American Folk Art Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists by CHUCK and JAN ROSENAK; (Abbeville Press, NYC, 1990)

Inez Nathaniel Walker—“I just draw by my own mission, you know. I just sit down and start to drawing.” BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Born Inez Stedman, 1911, Sumter, South Carolina. Received little formal education. Married (first name unknown) Nathaniel, 1924; married (first name unknown) Walker around 1972; separated. Three sons, one daughter. Died May 23, 1990, Willard, New York. GENERAL BACKGROUND Inez Nathaniel Walker began to draw her expressive, imaginatively colored portraits—usually of women—while she was in prison. Firm facts about Walker’s life are rare. It is believed that she was born in South Carolina, that her father died when she was twelve or thirteen years old, and that she was married to Nathaniel when she was around sixteen, but no confirmation of these dates or events is available. Walker is quoted as saying that she moved north around 1930 to escape the “muck” of farm work. She worked for a time in a pickle factory in Philadelphia and around 1949 moved to Port Byron, New York, where she worked on apple farms. In 1970 Walker was convicted of the “criminally negligent homicide” of a man who she felt had mistreated her. She explained her action with the statement: “Some of these men folks is pitiful.” Walker was incarcerated in the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, Bedford, New York, from 1971 through 1972 for her crime. After she was released from prison, Walker returned to the Port Byron area and farm work; there she married for the second time. ARTISTIC BACKGROUND Inez Walker started drawing in 1972 while she was in prison. Elizabeth Bayley, who taught remedial English at the Bedford Hills facility, showed some of her drawings to Pat Parsons, an art dealer. Parsons bought most of the drawings and befriended the artist; she is the last person Walker is known to have contacted before she disappeared. Parsons received a phone call from her on Thanksgiving Day in 1980, and no one heard from her again. SUBJECTS AND SOURCES Walker said that she drew to protect herself from “all those bad girls,” but it is not clear if she was referring to the inmates or other women she knew (nor is it clear whether the women in her drawings are supposed to be inmates or others). For the most part, Walker drew women in single or double portraits, sometimes full-length but mostly head-and-shoulder views. The women are shown looing straight ahead or in profile, sometimes talking, drinking, or smoking. Their eyes always face front, regardless of the position of their heads. Walker concentrated on her subjects’ hairstyles; the bodies are usually oreshortened and, when shown full length, have tiny feet, disproportionate to their body size. MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES Walkers first efforts were on the back of the mimeographed pages of the prison newspaper. Later Pat Parsons supplied her with first-rate materials—good paper, watercolors, pencils (both colored and graphite), ink, crayons, and felt markers. Walker did not concern herself with realistic color schemes; her faces and other visible areas of skin may be shown as solid red or blue, with details set off in black. The backgrounds contain boldly geometric and linear designs, and similar designs are often repeated on the subjects’ clothing. At some point after her remarriage, Walker stopped using “Nathaniel” on her drawings and began to sign them simply “Inez Walker.” Most of Walker’s drawings are about 17 by 11 inches in size. Some are larger, and approximately twenty of them measure 42 by 30 inches. Walker is known to have completed three or four hundred drawings in total. ARTISTIC RECOGNITION Inez Nathaniel Walker’s drawings are beautiful and timeless, and they deserve an important position in the history of clack folk art. Her work has been shown in exhiitions in New York, Ohio, Pennsylbania, and elsewhere and is included in the collection of the Museum of American Folk Art in New York City. |

From ART IN REVIEW; 'A Return to January 1982' -- 'The Corcoran Show Revisited' By ROBERTA SMITH, Published: March 8, 2002 The Corcoran show isolated for the first time the achievement of self-taught black artists, most of whom were born around the turn of the 20th century and lived in the South. Some of the works are more representative of their makers' achievements than others. Among the standouts are Inez Nathaniel-Walker's drawings of buoyant ballooning figures anchored by an airy assortment of patterns and textures, which particularize garments, surroundings, hair and race. Like Traylor, Nathaniel-Walker had a nearly infallible sense of placement, proportion and graphic expression. |

From Chuck and Jan Rosenak's Museum of American Folk Art Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists: Inez Walker Walker's first efforts were on the back of the mimeographed pages of the prison newspaper. Later Pat Parsons supplied her with first-rate materials: good paper, watercolors, pencils (both colored and graphite), ink crayons, and felt markers. Walker did not concern herself with realistic color schemes; her faces and other visible areas of skin may be shown as solid red or blue, with details set off in black. The backgrounds contain boldly geometric and linear designs, and similar designs are often repeated on the subjects' clothing. [Since her release from the correctional center in 1974, Inez Walker has returned to migrant farm work in upstate New York.] Most of Walker's drawings are about 17 by 11 inches in size. Some are larger, and approximately twenty of them measure 42 by 30 inches. Walker is known to have completed three or four hundred drawings in total. |

Jim Roche on the Artists in "Unsigned, Unsung, Whereabouts Unknown...Make-Do Art of the American Outlands:" (Boy that's a great title!) Over the years, it was the artists themselves as much as the work that fascinated me: the story of how the artists started or what got them going, the "make- do" part of it. Take what you have, bring it up to a supposed 'higher' style and celebrate something about your life. When you're talking about "Unsigned, Unsung, Whereabouts Unknown," that characterizes most of these artists, for sure, at one time in their lives. Some have come into prominence now, but at one time, they were completely obscure, no one, sometimes, not even themselves had any special faith in what they were doing. The appeal with Inez Walker is different. She is someone who didn't start working until something cataclysmic happened; the way I heard her story is that she's having a rough life, she's picking apples and she's hooked up with the wrong guy (who mistreats her). She says "the Hell with it!"--he dies in the house and charges are brought against her so that she has to go to prison. In prison there are remedial programs; she's not too easy to get along with and there are personality conflicts. She begins working and creates straight ahead confrontational drawings (much like she is). The idea that she would work, begin to generate, get out of prison and disappear points to the fact that something happened to her (but we don't know what). There have been rumors that she reappeared, though since the early '80s no one has really known where she went. Yet she left this wonderful, obscure body of work: "whereabouts unknown"--fits perfectly, here. (Jim Roche wrote this in 1993 as Professor, Department of Fine Arts, Florida State University, Tallahassee.) |

Reviewed in The New York Times, March 8, 2002, by Roberta Smith and Raw Vision, Summer 2002, by Edward Gomez, p.62: A Return to January '82: The Corcoran Show Revisited 22 January - 16 March 2002 The twenty artists in this exhibition were reunited to celebrate the anniversary of the Corcoran Gallery of Art's 1982 show, Black Folk Art in America 1930-1980. Originally found in areas removed from the mainstream venues of museums and galleries, these artists have moved steadily into a broader spectrum of acceptance and appreciation. The works shown here echo the unique aesthetics and surprising forms seen twenty years ago in an attempt to illustrate how much has changed around them and how differently they can be seen today. A Return to January '82 reflects on the seminal statement of the Corcoran's 1982 exhibition and its widespread legacy to the self-taught community within the art world today. Including Jesse Aaron, Steve Ashby, David Butler, Ulyysses Davis, William Dawson, Sam Doyle, William Edmondson, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Inez Nathaniel-Walker, Leslie Payne, Elijiah Pierce, Nellie Mae Rowe, James 'Son Ford' Thomas, Mose Tolliver, Bill Traylor, George White, George Willams, Luster Willis and Joseph Yoakum. |

INEZ WALKER.com

Web Site created 8 Nov 02

Hosted by Copyright 2002-2024, Don Bayley

|

| Bibliography: "Black Folk Art in America 1930-1980" by Jane Livingston and John Beardsley, published for the Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1982. "Museum of American Folk Art Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century American Folk Art and Artists" by Chuck and Jan Rosenak, Abbeville Press, New York, 1990. "20th Century American Folk, Self Taught, and Outsider Art" by Betty-Carol Sellen, Cynthia J. Johnson, Neal-Schuman Publishers, New York, 1993. "Contemporary American Folk Art - A Collector's Guide" Chuck and Jan Rosenak, Abbeville Press, 1996. "Flying Free: Twentieth-Century Self-Taught Art from the Collection of Ellin and Baron Gordon" by Ellin Gordon, Barbara L. Luck and Tom Patterson, exhibit catalog for The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, 1997. "Self Taught, Outsider, and Folk Art—A guide to American Artists, Locations and Resources" by Betty-Carol Sellen with Cynthia J. Johnson, 2000. “American Self-Taught Art: An Illustrated Analysis of 20th Century Artists and Trends with 1,319 Capsule Biographies” by Florence Laffal and Julius Laffal, 2003. “Wos Up Man?” Selections from the Joseph D. and Janet M. Sheen Collection of Self-taught Art” Palmer Museum of Art, 2005. Lynda Roscoe Hartigan. Made with Passion: The Hemphill Folk Art Collection in the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C. and London: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990). Slotin Folk Art Auction Catalog, Masterpiece Sale, November 4, 2006 Inez Nathaniel Walker drawings are in the Collection de l'Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, the L'Arcanie, Neuilly-sur-Marne, near Paris as well as in a number of museums in the United States such as the Museum of American Folk Art, the Museum of International Folk Art and the Smithsonian. Additional Museum Collections:

Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center

Inez Nathaniel Walker (born: Inez Stedman), Old Dominion University:

The Baron and Ellin Gordon Collection

of Self-Taught Art.

University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth

|

Search this Site: